The dream of resurrecting extinct species has long captured the imagination of scientists and the public alike. Among the most iconic candidates for de-extinction is the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, a marsupial predator that once roamed the wilds of Australia and Tasmania before being hunted to extinction in the early 20th century. Recent advances in genetic engineering and cloning technologies have sparked hope that the thylacine could one day walk the earth again. However, despite the enthusiasm surrounding this possibility, significant scientific hurdles remain, particularly in the realm of cloning technology.

The Thylacine’s Genetic Legacy

The journey to resurrect the thylacine begins with its DNA. Unlike dinosaurs, whose genetic material has degraded beyond recovery over millions of years, the thylacine’s extinction is relatively recent. Preserved specimens in museums and private collections still contain fragments of its genetic code. In 2008, scientists successfully sequenced a portion of the thylacine’s DNA from a 100-year-old ethanol-preserved pup, marking a critical milestone. However, assembling a complete and functional genome from these fragments is a monumental challenge. DNA degrades over time, even under ideal preservation conditions, leaving gaps and errors that complicate the reconstruction process.

Modern techniques, such as CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, offer tools to patch these gaps by borrowing sequences from closely related species, like the fat-tailed dunnart, a small marsupial with genetic similarities to the thylacine. Yet, this approach is far from foolproof. The thylacine’s unique biology, including its role as a apex predator and its distinctive reproductive system as a marsupial, means that even small genetic inaccuracies could have profound effects on the viability and behavior of any cloned offspring.

The Cloning Conundrum

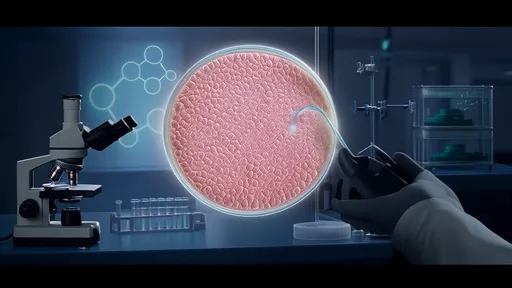

Assuming a complete and accurate genome can be assembled, the next hurdle is cloning. The most promising method involves somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the same technique used to create Dolly the sheep in 1996. In this process, the nucleus of a donor egg cell is replaced with the nucleus of a somatic cell from the species to be cloned. The egg is then stimulated to divide and develop into an embryo, which is implanted into a surrogate mother.

For the thylacine, this presents several problems. First, marsupial reproductive biology is markedly different from that of placental mammals like sheep or mice. Marsupials give birth to highly underdeveloped young that complete their growth in a pouch, relying on complex hormonal and physiological interactions between mother and offspring. Replicating these conditions in a surrogate from a different species—likely the dunnart—is uncharted territory. Even if an embryo could be successfully created, there is no guarantee that a dunnart’s reproductive system would support the development of a thylacine fetus to term.

Ethical and Ecological Considerations

Beyond the technical challenges, the prospect of de-extinction raises ethical and ecological questions. Critics argue that the resources required to resurrect the thylacine could be better spent conserving endangered species still clinging to survival. Others worry about the moral implications of creating animals that might suffer due to genetic abnormalities or the inability to thrive in a modern ecosystem vastly different from the one they once inhabited.

Even if a thylacine could be brought back, its role in today’s environment is uncertain. The landscapes of Tasmania and Australia have changed dramatically since the thylacine’s extinction, with introduced predators like foxes and feral cats altering the ecological balance. Reintroducing a long-lost predator could have unforeseen consequences, both for the thylacine itself and for the ecosystems it once called home.

The Road Ahead

Despite these challenges, research into thylacine de-extinction continues. Projects like the TIGRR Lab (Thylacine Integrated Genomic Restoration Research Lab) in Australia are dedicated to advancing the science required to make resurrection a reality. Collaborations between geneticists, reproductive biologists, and ecologists are essential to address the multifaceted obstacles standing in the way.

While the cloning of a thylacine remains a distant possibility, the pursuit of this goal drives innovation in genetics and conservation biology. Whether or not the thylacine ever returns, the lessons learned from this endeavor could pave the way for other de-extinction efforts or, more importantly, inform strategies to protect the biodiversity we still have. The thylacine’s story serves as a poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the responsibilities humanity bears in stewardship of the natural world.

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025

By /Aug 12, 2025